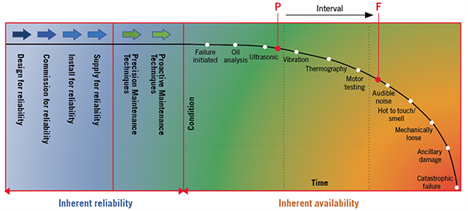

The P-F curve is a graph that helps visualize an asset’s condition to determine its practical lifespan. The most important element in the curve is the P-F interval. This is the period of time between the first point of potential failure to the asset’s functional failure, when it no longer meets a particular standard of performance.

The P-F curve is as relevant as ever for reliability professionals in 2022. Advances in technology have allowed us to develop maintenance tools designed to gauge an asset’s health based on a variety of variables: oil analysis, ultrasound, vibration monitoring, thermography, and motor testing.

Updated models of the curve often feature some of these measurement methods to better identify signs of wear and damage. This helps avoid failure and extends the life of the asset.

During a webinar by Fluke Reliability, 250 maintenance and reliability professionals from around the world were asked which of the five measurement methods they were using.

Here are the percentages of attendees who reported using each method:

- Vibration monitoring/analysis: 82%

- Thermography: 69%

- Oil analysis: 66%

- Motor testing: 54%

- Ultrasound: 36%

It’s not always necessary for an organization to use all five methods. Some industries and assets require being alerted to the earliest possible failure indicators, but some do not.

What Condition Monitoring Methods Should I Use?

Just as an effective maintenance and reliability program uses a mix of condition-based, calendar-based, and reactive maintenance, the P-F curve can be most beneficial when its use relies on a combination of variables.

Even companies with established condition-based maintenance (CBM) routines do not use them for every single one of their assets. Every organization must consider both an asset’s lifespan and the resources, such as labor hours and parts, required to prevent failures. For example, frequent inspections can detect indicators of failure early on but require time and availability to carry out.

So, which should you use? Condition monitoring expert Colin Pickett had this to say during another recent Fluke Reliability webinar: “Any condition monitoring (CM) program will likely include vibration analysis since it’s the most common and cost-effective CM solution. But you should also have other data collection methods or tools to help determine the condition of your machines.”

Below, we detail each of the five variables to help you make a smart choice. But first, here is some background on the P-F curve for those who may be unfamiliar with it.

The History and Definition of the P-F Curve Explained

The P-F curve was first introduced in 1978 by United Airlines engineers Stanley Nowlan and Howard Heap. They performed a study for the Department of Defense that showed that repairing or replacing assets based on the condition was more effective than doing so based on age.

The “P” of the P-F curve refers to potential failure, which is when an asset experiences an identifiable change in its physical condition. The “F” refers to functional failure, which is the point at which the asset fails to meet a predetermined performance standard. The asset may still be operational, but it is not running the way it was designed to.

The above version of the curve was developed by Fluke Reliability experts. It begins with Design for Reliability, Commission for Reliability, Install for Reliability, and Supply for Reliability. These are commitments made by the original manufacturer of the asset, whether it be you or a third party.

Past these stages, the P-F curve moves to Precision Maintenance Techniques and Proactive Maintenance Techniques. These are performed to ensure an asset reaches maximum inherent reliability.

Once an asset passes these stages, its condition is deteriorating, and failure signs begin to be detected. Again, failure itself does not mean that an asset is completely non-functional; that stage is not reached until catastrophic failure.

Common Signs of Machine Failure on the P-F Curve

One way to determine which variables to use for different assets is to refer to the original equipment manufacturer. They can be a valuable source for learning an asset’s most common failure indicators. Later means of failure detection can be done with simpler, non-intrusive techniques. Once the failure has been detected, and the cause has been identified, you can determine how to go ahead repairing or maintaining the asset.

It is possible to lengthen the time between when an asset is installed and when potential failure begins. Some maintenance teams talk about prolonging the P-F interval. If you ensure that components have the optimal fit, clearance, and alignment, some common types of failures can be eliminated and you can improve how assets perform.

The sooner a potential sign of failure is detected, the sooner you can schedule maintenance, and the more corrective maintenance activities can prolong an asset’s life. However, the methods that can detect failure is about to occur the earliest tend to require sophisticated types of equipment and even diagnoses from external labs.

Advancements in condition-based maintenance tools to gauge asset health – as well as added pressures from today’s competitive business environment – have made that old standby, the P-F curve, as relevant as ever for reliability professionals in 2022.

Five P-F Curve Variables to use in Determining Asset Condition

Now that we’ve got the P-F curved explained, including the history, definition, and importance, we can detail the five major variables to consider when inspecting an asset’s condition. Remember, not every variable will be applicable for every situation, so determine the most effective methods for you.

Here are the variables, presented in order from early on in an asset’s lifespan to later.

Oil Analysis

Oil analysis can determine the presence of lubrication breakdown, overheating, and component wear. These can be indicators of gear failure or bearing and cylinder wear. Oil analysis is commonly used on gearboxes, compressors, and other moving or rotating parts.

Oil analysis is an advanced method and may require a lab analysis for diagnosis. Oil temperature measurements can also be taken and analyzed. This method is more straightforward but less conclusive.

Ultrasound Leak Detectors

Ultrasound can detect sounds that human ears can’t. Ultrasonic leak detection can pinpoint problems with valves, steam traps, bearings, or potential electrical safety hazards.

Vibration Monitoring

Vibration is one of the most common and accessible methods of tracking an asset’s condition. Vibration monitoring can indicate four of the most common mechanical methods of failure: imbalance, misalignment, looseness, and bearing failure; among other, less common failures.

Vibration monitoring offers the ability to screen less critical equipment while performing time-based preventive maintenance. If a problem is identified, vibration monitoring or analysis can be performed.

Thermography

Thermography is recommended for time- or fault-based inspection routes, because after an asset has overheated, some damage may have already occurred. It can detect electrical and mechanical problems that have caused an asset to overheat, such as from misalignment, gearbox, or belt problems.

Motor Testing

Motor testing is used later in an asset’s lifespan. Different types of tests can be performed on motors depending on whether they are in operation. Insulation degradation, power factor, and harmonic distortion are all issues best detected while the motor is operating. Other tests look at a motor’s speed, torque, power, and efficiency.

Conclusion

Assets fail in different ways, and not all assets are equally critical to a plant’s production. Even within an asset, various components require different levels of urgency.

Therefore, combining tools and techniques is the most effective way to apply the P-F curve — one size truly does not fit all. Combined with useful data and analysis, the P-F curve can help organizations continuously improve their maintenance strategies and increase their assets’ reliability.

About the Authors: John Bernet, Gregory Perry, and Dries Van Loon

John Bernet, CMRP, is a mechanical application and product specialist with Fluke Reliability and has over 30 years of experience in preventive maintenance, predictive maintenance, condition monitoring, and the operation of commercial machinery.

Gregory Perry, CMRP, CRL, is senior capacity assurance consultant with Fluke Reliability. He has been a Certified Reliability leader with nearly two decades of experience in preventive maintenance, reliability-centered maintenance (RCM), and operational best practices.

Dries Van Loon, CRL, is sales and project manager, online condition monitoring, for Fluke Reliability, with 10 years of predictive maintenance experience. He became a certified ISO CAT 4 analyst in 2017.